Issue 12.03 - March 2004

The Complete Guide to

Googlemania!

They named their new search engine Google, for the biggest number they could imagine. But it wasn't big enough. Today Google's a library, an almanac, a settler of bets. It's a parlor game, a dating service, a shopping mall. It's a Microsoft rival. It's a verb. At more than 200 million requests a day, it is, by far, the world's biggest search engine. And now, on the eve of a very public stock offering, it's cast as savior, a harbinger of rebirth in the Valley. How can it be so many things? It's Goooooooooogle.

By Wired Magazine

Surviving IPO Fever

What

it's like inside the white-hot quiet period.

By Michael S.

Malone

Photo by Michael Grecco

Larry

Page, left, Google cofounder and president, products; Sergey Brin, right,

cofounder and president, technology.

This year's hot IPO is, of course, Google. The company has everything its famous predecessors had and then some: consumer loyalty, top-drawer technology, profits, and promise. "There are good IPOs, and there are great IPOs," says Marc Andreessen, a veteran of the public-offering process at both Netscape and Loudcloud (now Opsware). "The Google IPO is the rarest kind: one that draws the white-hot glare of public attention."

This is more than what the bankers like to call a liquidity event. Already, the Google IPO seems to be heralding a great new round of public offerings - by late January, 26 tech companies were registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission, according to financial research firm Dealogic, all apparently waiting for Sergey Brin, Larry Page, and Eric Schmidt to prime the pump. Market watchers say Google could start issuing stock as soon as this spring, and in many ways the company is behaving as though the quiet period has already begun. What hungry investors (and unemployed tech workers) really want out of Google can best be summed up by a bumper sticker out on the highways of Silicon Valley: just give us one more bubble.

IPOs are like dreams: sometimes happy, often irrational, usually quixotic - and fraught with unexpected twists. Sometimes they turn into nightmares. (This magazine's founders, for example, twice spectacularly failed to take their rocketing venture public.) There's good reason for this. The typical firm entering the public market is less than five years old with a generation or two of products under its belt. The company is newly profitable (if at all) and only recently established a serious financial reporting apparatus. Meanwhile, it's growing like topsy and adding scads of employees with little idea of its core philosophy and business practices. The firm speaks with multiple voices, at cross purposes; some founding employees begin muttering about how the place is going to hell. Simply put, most companies at their debuts are adolescents - arrogant, self-conscious, hormonal, healthy, but also very, very fragile.

Then comes that pesky quiet period. It's bad enough for the Googleans to have the weight of the entire stock market on their shoulders. One slip of the tongue - a prediction of the opening price, an unscheduled product announcement - and the whole thing's toast. Which means these days everyone inside Google is scared to say anything about anything. As they should be. In this post-Enron era, SEC regulators are watching Google's every move, reading every public statement and keeping an eye on all our favorite magazines and newspapers. If Google is going to be the first of a new round of IPOs, it will be a model of responsibility.

But there are some pre-IPO truisms that, taken together, can paint a clear picture of what's happening inside Google right now. For example, it's a good bet that the VCs and management are at each other's throats. This is a simple matter of conflicting interests. VCs, desperate to prop up sagging portfolios with a big win (and then, needless to say, cash themselves out), are constantly exerting pressure to go public. Top managers naturally resist, since being a public company represents a new level of drudgery, exposure, and restriction. Many observers suspect this is why CEO Eric Schmidt put off the IPO so long.

Once a company registers with the SEC, business as usual ceases. The days of easy improvisation are over. The already overburdened and understaffed senior management team gets cut in half. Team A deals with underwriters and attorneys, revises the prospectus - vetting every word 50 times - and embarks on a grueling 20-city, five-continent road show. Team B hangs back to manage the unmanageable. "I was the guy who got to stay home," says Jeff Skoll, eBay's first employee and former president. "Even with all the management on hand, the company was growing too fast. Now it was absolute bedlam. An emergency would land on my desk, and before I could respond to it, another emergency would appear."

None of this gets lost on the rank and file, who've been quietly predicting the IPO date for months. Now that the event is officially on, they can think of nothing else. Every assistant, every product marketer, becomes an amateur historian and stat-spewing analyst, looking at past precedents and current financial environments to guess where the stock will open and how high it will climb (it always climbs) in the weeks and months to come. Then, satisfied they've nailed the stock's fate, employees take a momentous and inevitable next step: They multiply the fate by the number of shares they own to come up with their financial destiny.

At this point, there is no going back. Every relationship in the company has now changed. The high-ranking and the early-hired crack little smiles throughout the day as a six- or seven-digit number pops into their minds. Those with fewer options put on a good face and seethe. The real volatility comes when two org-chart peers rub shoulders. The early-vesting, longtime employee looks forward to Monaco and a Maserati, and the other to 20 more years in a cubicle and a gold watch.

Once this great financial destiny is fixed in employees' brains, woe betide the company that reverse-splits its stock to reach a target opening share price. That's what chip manufacturer Mips did in 1989, and the company fell into a funk for two weeks. Wired has learned that Google did the opposite - a stock split. There was a run on champagne at every liquor store in Mountain View that night, I can assure you.

Weeks before the IPO, the company dissolves into a pantomime show - a fevered, desperate attempt to present an image of normalcy to the world and to itself. But it never works, because things are anything but normal. Reporters phone-bomb everybody even remotely connected to the company, hoping to find the bozo who'll deliver the money quote. "I remember landing at SFO and running into these scrums of camera crews and reporters," says Andreessen. "That kind of world is for movie stars, not for normal people."

To the outside world, the people going through the IPO are Lotto winners. "I remember coming in one morning and having 50 phone messages," says semiconductor industry veteran K. C. Murphy. "One was from a reporter, the other 49 were from bankers offering to help me invest my money."

In the last few weeks before

Going Public Day, the company descends into a bunker mentality. Employees keep

to themselves - veterans stick with veterans, rookies with rookies - and one's

most wistful thoughts about the future are now reserved for late at night, in

bed, with one's spouse. "What I remember most," says Skoll, "is that in all that

craziness there was also a feeling of unity. We all were so optimistic. The

business hadn't yet been tainted by money. It was a real golden period."

Photo by Michael Grecco

Eric

Schmidt, CEO

Going Public Day itself is generally something of an anticlimax. Barring the unexpected disaster - an underwriter shoots his mouth off to the press, the stock market goes into freefall, the SEC discovers a filing anomaly - at some point that morning, usually very early California time, a unique cluster of letters appears on a computer display followed by a number. The little startup is now a publicly traded corporation, heir to the legacy of IBM, General Motors, Hewlett-Packard.

In conference rooms, knots of people raise glasses, laugh and cry spontaneously, slap each other on the back, hug, and make plans for dinner and endless rounds of drinks. Some are tycoons, most are worth more now than anyone in their family has ever been. They tell each other that they won't let it affect their great company, God bless it, and swear that they, too, will not change. Most of all, they're relieved it's finally over.

But it ain't. In the history of most great companies, the buildup to the IPO is chapter one of a very long book. "For companies, going public is a fundraising event," says Andreessen. "For the cultures of those companies, it changes everything."

The company has entered the world of quarterly earnings statements, analyst conference calls, shareholder meetings, and annual reports - the kind of financial bureaucracy that officially puts an end to the spur-of-the-moment decisions that characterized the startup phase. This change, more than anything else, ultimately will drive away the founders of the company. "Within a couple years after going public, basically all of the early people at eBay were gone," says Skoll.

As the founders leave, the workforce starts to look rather different. Startups attract risk-takers, men and women willing to accept long hours and smaller salaries for the chance to create something great and get rich in the process. Public corporations attract people less interested in the big score than the big office. Free-flowing founders' stock is replaced by disciplined stock option programs. New ideas are replaced by new initiatives.

"Before we went public, I used to send out a company-wide joke each day, just as a way of loosening things up," says Skoll. "The day after the IPO, I sat down at my computer to write that day's joke and in walked the general counsel. He says to me, 'You know that joke of the day thing? I think it's very funny.' Gosh, thank you, I replied. 'Well, stop it,' he said. 'We are a public company now, and we don't want to offend anyone. If you want to keep sending out jokes, they can only be about lawyers.' So I tried sending out lawyer jokes for two weeks - and then I gave up."

This isn't all bad. For one thing, not all startups make great, gutsy choices and end up changing the world. More often they make stupid, impetuous decisions and die. Big public companies rarely do really dumb, suicidal things. Rather, they go on for generations, providing a livelihood for thousands.

But what of the first employees, those people out celebrating their Going Public Day wealth? Tough to say. Each will handle it differently, guided by their own heart. The most famous IPO story is that of Dennis Barnhart, the Eagle Computer CEO who, on the day his company went public in 1983, went to a celebratory lunch with his yacht dealer, then pointed his new Ferrari toward home - only to crash to his death off a hillside in Los Gatos, California. "There is no predicting human behavior, especially around an IPO," says Millard. "People do very weird and unexpected things when it comes to money."

There are as many cautionary post-IPO stories in the tech world as there were medieval morality plays. A few calls to Valley veterans revealed:

The quiet code writer rarely seen outside his cubicle who suddenly takes to wandering the halls and bursting in on the CEO's private meetings until he is summarily fired.

The mousy guy in accounting who dumps his mousy wife and runs off to Mexico with the admin.

The lonely programmer who goes off to a men's club to celebrate his new wealth and marries a stripper he meets there.

The sober family man who, upon discovering that he's half-Native American, renounces his US citizenship and moves to an Indian reservation so he won't have to pay taxes.

The programmer who quits, buys the sports car of his dreams, crashes, loses everything in the resulting personal-injury lawsuit, and ends up broke, back in his old job.

Google

executives will warn their charges against doing anything so rash. Before the

eBay IPO, founder Pierre Omidyar held up a chart at a company meeting showing

Yahoo!'s roller-coaster market capitalization of the previous two months as a

way of telling his employees to ignore price swings. Yet, within weeks, so much

productivity was lost to people staring at financial Web sites all day that CEO

Meg Whitman announced she'd fire anyone she saw totaling up their wealth.

GOOGLOSSARY

Google dance

the update of the Google

index, completed every 20 to 30 days.

Florida

what webmasters call the latest

version of the Google index.

Google

juice

a property of a site that enjoys a high ranking on

Google.

Google whack

a results page

featuring only one return, obtained by querying two words, no

quotes: hobo matureness, gigolo whitethroat.

Google

bomb

when multiple Web sites use an identical phrase

(e.g., "miserable failure") hyperlinked to the same URL

(www.

whitehouse.gov/president /gwbbio.html), with the intent of

pushing it to the top of a Google results page. Also used by

bloggers to elevate their own sites.

Google

hole

the state of having been led astray by Google

results.

Googlegänger

a doppelgänger,

identified by Googling oneself; generally used with derision or

jealousy.

Google Doodle

the occasional

re-rendering of the Google logo for major holidays, the birthdays of

famous historical figures, et

cetera.

kilogoogle

a unit of measurement

equal to 1,000 Google hits.

Googlopoly

the state of dominating the

Internet search

space.

K. C. Murphy gave a similar talk at one of his semiconductor companies. "Within two weeks, out of 75 employees, five had big new houses and two more had bought luxury cars." At another of his firms, employees were using options as collateral to borrow money. Others forgot about the capital gains taxes. When the stock slumped, they found themselves with more tax debt than net worth.

Two things are certain with Google's IPO: First, everyone will privately swear not to do anything brash, ostentatious, or tacky. Then, within days after the IPO, Google's parking lot will look like a showcase for German automotive engineering - just as it did at Apple and Netscape. A few Googleans have no doubt already placed their orders.

It's easy to think of a mega-IPO as a corporate event, but corporations are of course made up of people. A public offering on the order of Google's is the ultimate character challenge for everyone with a company badge. (And, given the emerging rules on expensing stock options, this could be technology's last great IPO event.) How they handle this test will determine the fate not only of Google but of their own lives. It will also very likely determine the strength and duration of the economic expansion that follows. In the tech world at least, the Google IPO will define the decade.

Have Schmidt and his team built a company that can survive the coming shock and remain focused and productive? Can it make the transition from startup to public company without losing its soul? Can the employees keep their perspective and still put the success of Google foremost - at least for a while longer - until the next, corporate generation of employees arrives?

It sounds impossible. And maybe it is. But impossible is exactly what we need right now.

Longtime Silicon Valley journalist Michael S. Malone (msmalone@aol.com) wrote about Google's search ticker in Wired 11.05.

Googlemaniacs

Nine

Superusers sound off.

- Matt Groening,

creator and executive producer, The Simpsons

"Google means that I no longer have an excuse to be ignorant. You can't

go into meetings unprepared anymore! I have a Google sticker on my computer

that, when I go through airport security and take out my PC, the security guys

see and act like I have a cute baby or something: 'Ooh, Google!'"

-

Esther Dyson, chair, EDventure Holdings

"Writers of the past had absinthe, whiskey, or heroin. I have Google. I

go there intending to stay five minutes and next thing I know, seven hours have

passed, I've written 43 words, and all I have to show for it is that I know the

titles of every episode of The Nanny and the

Professor."

- Michael Chabon, author, The

Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay

"Actually, Google has had zero impact on my life."

- Steven

Brill, Court TV founder and magazine entrepreneur; author, After:

How America Confronted the September 12 Era

"I

can't imagine life without Google News. Thousands of sources from around the

world ensure anyone with an Internet connection can stay informed. The diversity

of viewpoints available is staggering."

- Michael Powell,

chair, Federal Communications Commission

"Google rocks. It raises my perceived IQ by at least 20 points. I can

pull a reference or quote in seconds, and I can figure out who I'm talking to

and what they're known for - a key feature for those of us who are name-memory

challenged."

- Wes Boyd, president, MoveOn.org

"Google has improved my sex life, tightened my abs, and brought me closer

to God. (I keed.) Actually, as a working gossip columnist, I appreciate Google

as a rough - very rough - research tool. The Internet is still the Wild

West."

- Lloyd Grove, columnist, New York Daily

News

"My

version is exactly what it is now. Google has got it right."

- Edward

Tufte, Yale Professor of political science, computer science,

statistics, and graphic design

"Google is my rapid-response research assistant. On the run-up to a

deadline, I may use it to check the spelling of a foreign name, to acquire an

image of a particular piece of military hardware, to find the exact quote of a

public figure, check a stat, translate a phrase, or research the background of a

particular corporation. It's the Swiss Army knife of information

retrieval."

- Garry Trudeau, cartoonist and creator,

Doonesbury

"Within the last seven days, Google has altered and augmented my

perceptions of tulips, mind control, Japanese platform shoes, violent African

dictatorships, 3-D high-definition wallpaper, spicy chicken dishes, tiled hot

tubs, biological image-processing schemes, chihuahua hygiene, and many more

critical topics. Clearly, thanks to Google, I am not the man I was seven days

ago."

- John Gaeta, visual effects supervisor, the

Matrix trilogy

I'm Feeling Lucky:

The Engineer

Photo by Erik Pawassar

Where do you go after

Mars? To Google. At the NASA Ames Research Center in Mountain View, California,

Peter Norvig oversaw the coder team that in the late '90s taught rovers to find

their way across the Red Planet. A true accomplishment - though he's better

known for the wry PowerPoint version of Lincoln's Gettysburg Address that became

an Internet hit in 2001. Not long after, Norvig decamped NASA to become Google's

director of search quality. His mission: Enhance Google's software so it doesn't

just give users the results they ask for but leads them to answers they don't

know are there. - Paul Boutin

The Optimizer

Photo by Ian White

Psst … wanna buy

top-tier advertising on Google, cheap? Then check out what Bruce Clay is

hawking. He's part of a subset of Internet marketing specialists known as search

engine optimizers. Give Clay several grand and he'll guarantee you high

placement on results pages all over the Web. He claims that by adjusting a

site's content (primarily through keywords) he can double its monthly search

engine traffic within 90 days. And these clicks aren't generated from paid ads.

Free advertising - that's almost as good as free cable. - Jesse Freund

The User

Photo by Allan Penn

Most marathoners rely on

a good pair of sneakers and a high-carb diet. Monique Maddy had that much and

Google. She wasn't prepared for the New York City Marathon, though she had

qualified by running especially fast in her local Boston Marathon. Thanks to

Google, Maddy found herself 7,000 miles from home and 8,000 feet above sea level

doing sets of 20 grueling climbs up a 1,300-foot hill in a forest outside

Eldoret, Kenya. "I ended up training at the High Altitude Training Center in

Kenya with Lornah Kiplagat, one of the world's top female distance runners," she

says. "Google changed my life as a runner." - J.F.

4 Scenarios for the Future of

Google

Sometimes a liquidity event changes

everything.

By Tom McNichol

![]()

The long-awaited Google IPO

is a smash success, making billions for the company and investors. Market cap

soars, and the press declares the Google Revolution under way. But the reign

turns out to be short-lived, as a proprietary search engine from Microsoft

strong-arms the market and passes Google. Swimming in red ink, the company is

put on the selling block and becomes a wholly owned subsidiary of

AOL.

![]()

The long-awaited Google IPO is

a smash success, making billions for the company and investors. Flush with stock

earnings, Google's top tier of executives leave to "pursue other interests."

Rudderless, the firm goes on a spending spree, snapping up enterprises that add

little to the bottom line while at the same time fending off takeover attempts.

Google unveils a new executive team to help the company "find its way

again."

Google achieves platform-style

success, spawning a new industry where millions of bloggers depend on its ad

placement service as their primary source of income. Google becomes the second

most recognizable brand after Coke. "I'm feeling lucky" becomes a national

catchphrase. Rivals complain that Google squeezes out competition, but no one

seems to care. The courts begin to hold the company liable for all sorts of

wayward transactions.

![]()

Google's share of the search

market soars above 90 percent, and the company takes full advantage of its

position. Struggling search engines are either strangled or bought. Hardware

makers begin shipping computers loaded with the Google operating system. The

Department of Justice launches an investigation into the conglomerate's alleged

monopolistic practices. Popular bumper sticker: satan uses google.

The (Evil) Genius of Comment

Spammers

Renegade bloggers played Google for the

fool. Then the Web fought back.

By Steven

Johnson

The bloggers hit with these strange messages were victims of an insidious new species, now called "comment spam." But this was a strange sort of spam: Why would someone go to the trouble of spamming thousands of blog pages to deliver only glad tidings and hollow compliments?

The answer, oddly enough, is that the spammers weren't trying to win the attention of the bloggers or their readerships. They were trying to win the attention of Google, like the high school bully beating up the class nerd to impress the homecoming queen. The nerd feels violated, but the truth is that it isn't really about him at all.

The spammers were exploiting the fact that open comment forums on the Web let bloggers post HTML for free. And not just any Web pages: These are heavily valued by Google's PageRank algorithm, thanks to the chronic interlinking of the blogosphere. If you could convince one of those bloggers to link to your new site, you'd have instant credibility. And if you could persuade dozens of bloggers to place links, you'd be an overnight PageRank sensation. Because so much of the Web's traffic now funnels through Google's search engine, that higher ranking translates directly into more "customers" for the spammer.

The (evil) genius of the comment spammers came when they realized that actually persuading the bloggers was unnecessary. All you have to do is post some benign text in the comment field and include a URL for your gambling site or Viagra emporium in discreet HTML. It doesn't hurt that some popular blog formats - notably Movable Type - have a standardized URL for posting comments, making it much easier to automate spam creation. The ultimate goal, of course, is to win the PageRank arms race against your competitors so the next time some hopeful soul types "penis enlargement" into Google, your site will arrive at the top of the list, having been validated by the sudden flood of links from the blogging community.

Comment spam proliferated throughout the blog sites with amazing speed. One blogger had 120 posts spammed over four days. Thoughtful discussion spaces were besieged by meaningless posts, sometimes in broken English, sometimes with bizarre keywords inserted into otherwise prosaic comments in a sort of spammer Tourette's: "I greatly appreciate atkins diet the comments here."

Skilled technicians who were angered by the incursions, the bloggers began to fight back. Within weeks of the comment spam explosion of late 2003, the blogosphere had strategies for stopping or neutralizing the invading hordes, most notably a plug-in created by blogger Jay Allen that blocks all comments that include text culled from an ever-expanding blacklist of spammers. In January, Movable Type's creators released a special update that contained fixes designed to thwart comment spam, including one that makes URLs posted in comment threads invisible to PageRank.

In a way, the rise of comment spam confirms what many of us have felt for years: Google has become part of the Web's infrastructure, as central as HTTP or packet switching. The centrality has been a boon: PageRank has let us feel that information we seek is at our fingertips. But in a kind of dialectical progression, that very success has bred its own antithesis. Build a universe where linking determines relevance and where relevance leads to financial reward, and sooner or later people link in bad faith. Can PageRank learn to tell the difference?

Contributing editor Steven Johnson (stevenberlinjohnson@earthlink.net) is the author of Mind Wide Open: Your Brain and the Neuroscience of Everyday Life (Scribner).

It's an Ad, Ad, Ad, Ad

World

Forget the search business. Today Google's all

about advertising.

By Josh McHugh

Google didn't buy in - a stubbornness that

proved brilliant. Six years later, those skinny little text-based ads are a huge

moneymaker, accounting for more than $600 million in revenue last year,

according to Forrester Research. And Google, once simply the world's best search

engine, is fast reinventing itself as an advertising company.

Photo by Robyn Twomey

Susan

Wojcicki, director of product management

At the heart of the new Google is AdWords, a self-service ad server that uses relevance-ranking algorithms similar to the ones that make the search engine so effective. Advertisers tell Google how much they want to spend, then "buy" pertinent keywords. When users type in a matching term, the ad appears near the search results under the heading "Sponsored Links." Each time a user clicks on the ad, Google subtracts the cost-per-click from the advertiser's account. When the account's daily budget is met, Google stops displaying the ad.

So far the system has proven easy to use and remarkably effective. Roughly 15 percent of ads displayed adjacent to Google searches (at the company's own Web site and on Google-powered sites like Yahoo! and AOL) result in clickthroughs - more than 10 times the click rate of the average banner ad. These clickthroughs are the golden leads of online commerce. One Dow Chemical business group reported 25 percent of its traffic comes through Google. Designer Hospital Gowns, a health care industry Web site, boosted sales 20 percent in six months.

AdWords has worked so well that last year Google began offering the system to other sites as a way for them to provide targeted ads. The new service, AdSense, places ads on Web sites of all stripes, from ABC.com and The New York Times on the Web to quirky blogs like Bananathing!

Pinpoint targeting has always been the goal for advertising, but has been unattainable for a couple of reasons. First, content providers have rarely been able to deliver to marketers enough well-described and narrowly focused consumers. Second, even when marketers get the perfect audience, they rarely have targeted ads; it costs too much to make multiple variations for micro-audiences. AdSense strips away these barriers.

Since people reading blogs or news sites are less likely to be in purchase mode, AdSense clickthrough rates are lower than 15 percent but still far better than banner clickthroughs. Best of all for Web site owners, the investment is minimal: A few minutes to sign up and a little space at the top, side, or bottom of your page, and poof!, you're a local affiliate, taking in a few cents on every clickthrough. More than 150,000 sites have joined the syndicate so far. n

All of which makes Google an advertising company - though hardly in the typical Madison Avenue model. While most of the $500 billion ad world fixates on high-touch branding - spots designed to imprint a name on a consumer's mind - Google is going after low-profile but lucrative segments once lorded over by business directories and newspaper classifieds. Consider the $25 billion Yellow Pages business. Google recently added the location of a searcher to its blend of relevance factors, so if you query "Guinness keg," you won't see ads for liquor stores and distributors in some far-off city. "Branding has its place, but we're not focused on that," says Susan Wojcicki, director of product management. "We're selling very qualified leads."

Of course, even the best-laid algorithms can backfire. In December, two Verizon ads appeared on the New York Times site just inches below a commentary accusing Verizon of stealing from customers. Ouch. And to please big clients, Google has had to venture way, way beyond search into the uncomfortable (for engineers, anyway) world of schmoozing: Spend $10,000 per month and you'll get an entire Google account team at your service.

Such are the concerns that come with growth. Fact is, the company's statistics-driven approach to marketing has cracked a new category of customers and shifted the very notion of advertising from a blind bet to a quantifiable investment. Nineteenth-century retailer John Wanamaker famously complained that he knew he was wasting half of his advertising - but didn't know which half. Maybe he was just born too early.

Contributing editor Josh McHugh (josh@wiredmag.com) wrote about TiVo in Wired 11.10.

The Secret R&D

Army

How hackers give Google its wildest

ideas.

By Jeffrey M. O'Brien

That's why, almost two years ago, the company released a chunk of code called the application program interface. The API enables developers to build apps around Google search. By making the API freely available to any noncommercial site, Google hoped to inspire a community of programmers - smart, innovative, unpaid - to extend the engine's reach. It's working. "We get clever hacks, educational uses, and wacky stuff," says Nelson Minar, who runs the API effort. "We love to see people do creative things with our product."

What do developers get out of it? Officially, access to 3 billion Web pages. Unofficially, well, Google is bound to have some IPO billions left over for acquisitions. Here's a glimpse of a few of the best Google API apps out there.

Banana Slug (http://www.bananaslug.com/) When you've hit a dead end on a Google search, try Banana Slug. The site adds a random word to your search from one of nine categories - Themes from Shakespeare, Jargon Words, Animals - to generate surprising results. Add "groundhog" to your "eternal wisdom" query, for example, and you find a sermon from Reverend Robert A. Hill on why Groundhog Day is the best holiday. Now, that's word from on high.

CapeMail (capescience.capeclear.com/google/index.shtml) So your smartphone has Net access. Cool. Too bad it's a crappy way to surf the Web. Thanks to the Google API, CapeClear lets you search from your email program. Type your query into the subject line, fire it off to google@capeclear.com, and receive the results in your inbox.

Cookin' With Google (www.researchbuzz.org/archives/001404.shtml) Step one: Survey the fridge - scallions, last night's shrimp, half a head of broccoli, and a week-old orange. Step two: Type it all into the search box, hit Send, wait 0.3 seconds, and get 65 recipes that make use of your leftovers. Now you're eating Moroccan shrimp, rice, and orange salad - and cookin' with Google.

Google Alert (http://www.googlealert.com/) Researching a thesis on sea turtle devastation? The old way: Scour the Web repeatedly for new info. The new way: Have Google Alert do an automated search for you every day and return the results by email or RSS feed.

RateMyProfessors.com (http://www.ratemyprofessors.com/) The mission was admirable: Create a site that allows college students to rank their teachers. The problem: Too many jokesters typing in "Professor Hugh Jardon" and "Professor I. P. Freely." So the developers turned to the Google API to create an automatic verification tool. If Google finds enough mentions in conjunction with, say, "PhD" or "university," a professor makes the cut. It's a whole new kind of tenure.

How to Kill Google

Want

to topple the Web's darling? It's simple - build a trillion-page, ad-free,

up-to-the-minute search engine for everything ever put on the

Net.

By Paul Boutin

Crawl 'em all

Google has 3 billion pages in its

database, with AlltheWeb and Inktomi close behind. But there may be a trillion

more pages hiding in plain sight - in online databases such as WebMD and The

New York Times' archive, and they can't be reached by hopping from one link

to another. To get at them, a search engine needs to submit a query to each

site, then consolidate the results onto one page. CompletePlanet lets visitors

search more than 100,000 such databases, but only a few subjects at a time. No

current service is powerful enough to churn through all trillion possible

results at once.

Keep 'em all

Google is fast replacing Lexis-Nexis as

the research tool professionals turn to first. But Google lets you search only

its most recently crawled version of the Web. Pages that were changed or deleted

prior to the last crawl are lost forever. The Internet Archive's Wayback Machine

preserves a fraction of the Web's page history. What if you could search every

version of every page ever posted?

Follow the feeds

News sites and blogs are

supplementing their pages with RSS feeds - a service that pushes new content to

subscribers as soon as it's published. Google doesn't track RSS feeds, and

bloggers gripe that their posts take two to three days to show up in search

results. An engine to which Web site owners could upload RSS would provide the

latest version of every page.

Don't give away the formula

When Google debuted in

1998, its search results were free of the marketing pages that clogged other

engines. Even though Sergey Brin and Larry Page had published their PageRank

formula while at Stanford, it was tougher to fool than other scoring systems. In

2000, Google gave out a free PC toolbar that displayed the PageRank value of any

Web page, unwittingly handing Google gamers a cheat sheet.

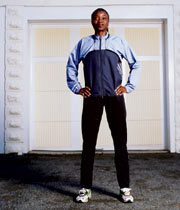

"How Would You Redo the Google

Interface?"

Four designers share their

(re)visions.

Joshua Davis

Joshua Davis

Graphic

designer

"The concept is simple: Map real physical information to the virtual

space of the Internet. Design guru Edward Tufte let me use him as my test

subject. A search of his name returns info from the domain registry's Whois

database. From that, we know Tufte lives in Cheshire, Connecticut, and the page

would pull in details about his actual surroundings. This alone brings a bit of

physicality to a domain."

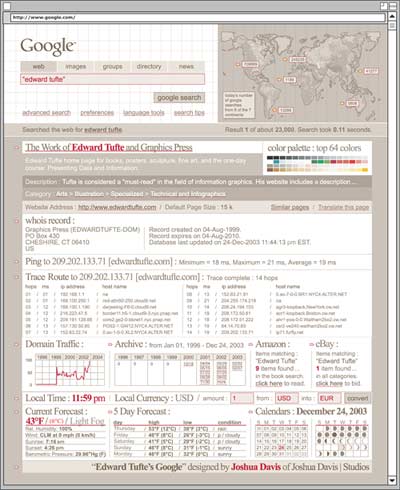

Jenny

Holzer

Photo by John Deane

Jenny

Holzer

Artist

"I'd provide a secret, a surprise, every time

someone visits Google. The user would get the covert stuff that makes fate. The

homepage might include a declassified report on Kuwaiti UFOs, a national

security directive (shown here), the express wish to see the Bushes in the White

House from Enron's Ken Lay, or a 1984 State Department "Where in the world is

Rumsfeld?" document that questions whether then-envoy to the Middle East Donald

Rumsfeld was somewhere in Iraq or perhaps back at his Searle job. All the

documents would be real and available on the Web."

Shepard

Fairey

Shepard Fairey

Propagandist, artist, designer

"I wanted to respect the

branding and format that Google has established, and therefore I stuck with the

structure of its interface to avoid user confusion. I like its simplicity, but I

don't like the colors. It needs to encourage more of an emotional attachment

with the user. I'm surprised they never thought to turn the o's into an infinity

symbol. The number Google is finite, but it's so large that it is infinite for

all practical purposes."

Ideo

Product and innovation firm

"'The Google

button. It's your trusted link to relevant information anywhere.' This concept

moves Google from World Wide Web to world-at-large. It positions Google as a

global infrastructure that provides a physical, context-aware link to relevant

information. By taking advantage of context, Google can provide targeted

information in almost any capacity."

Google vs. Gates

They're

obsessed with success and each other. Call it a (death) match made in

heaven.

By Kevin Kelleher

Like Oracle, Google is a category killer. Like Apple, Google has brand cachet and a loyal following. Like Netscape, it has the energy of youth and is touted as the trigger for the next tech boom. Meanwhile, Microsoft remains, well, Microsoft. Big. Strong. Rich.

Until recently, the mutual admiration and fear between the companies was reserved for board meetings and cubicle chatter. Now it's open to the public. In the spring of 2002, Google introduced an engine tailored to search Microsoft-related Web pages. Then Microsoft indicated in early 2003 that it would revamp MSN Search to return faster, algorithmically driven results without banner ads - à la Google. A few months later, Google moved further into Microsoft territory with the Deskbar, a search box that sits on the Windows OS. Come fall, Microsoft reportedly bid $10 billion to buy Google, but the offer was spurned. At the World Economic Forum in January, Bill Gates weighed in. "They kicked our butts," he said - then quickly declared that Redmond's next-gen engine would out-Google Google.

Why is Microsoft so obsessed? Because it knows search is a key component in the future of computing. Microsoft's next-generation OS, Longhorn, is conceived as a unified interface for a PC, its local network, and the Web. For it to work, Longhorn needs a sleek search utility. If Microsoft can't buy Google, it'll resort to its time-tested strategy: copy the best technology and integrate it on the desktop.

At the same time, Google has become more than a typical search engine. Its search box is a phone book and a dictionary. It can check stock prices, provide news, track FedEx packages, perform metric conversions, locate airplanes, offer street maps, and supply weather conditions. It'll search retail outlets by zip code and, with Froogle, scour the Web for products. In short, Google execs are innovating like they're running from someone. "People at Google don't talk about it, but it's pretty evident," says Danny Sullivan, editor of Search Engine Watch. "Microsoft's making a move into search that's equal to its move into Web browsers. That's got to make you nervous."

For all their differences, the two companies have a lot in common. Microsoft looks at Google and sees its own past, full of promise. Google looks at Microsoft and sees the future - a swaggering company that dominates the tech landscape. It's a classic battle between youth and experience or, as Google likes to believe, good and evil.

Kevin Kelleher (kpk99@yahoo.com) wrote about Java in Wired 11.12.

Copyright ©

1993-2003 The Condé Nast Publications Inc. All rights reserved.

Copyright © 1994-2003 Wired Digital, Inc. All rights reserved.