The Rabbi Shergill Experience

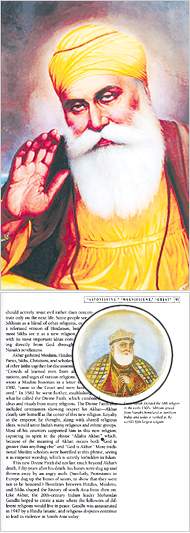

Three years ago, Indian singer-songwriter Rabbi Shergill exploded on the Indian alternative pop scene with "Bulla Ki Jaana," a distinctively spiritual -- and yet extremely catchy -- hit single. The song was unusual because it took the words of the Sufi poet Bulleh Shah, and gave them a modern context. And Rabbi Shergill was himself unusual (even in India) to be a turbaned, unshorn Sikh, making a claim on popular music with a sound that has nothing in common, whatsoever, with Bhangra. From my point of view Rabbi has been a welcome presence on many levels -- most of all, I would say, because he seems to aspire to a kind of seriousness and thoughtfulness in the otherwise craptastic landscape of today's filmi music (think "Paisa Paisa" from "Apna Sapna Money Money"; or better yet, don't don't).

After a few years of silence (disregarding, for the moment, his contribution to the film Delhi Heights), Rabbi finally has a follow-up album, Avengi Ja Nahin (which would be "Ayegi Ya Nahin" if the song were in Hindi). The album is available at the Itunes store -- so if you're thinking of getting it, it should be easy enough to resist the temptation to download it illegally off the internets.

The video for the first single, "Avengi Ja Nahin", can be found on YouTube:

I'm personally not that excited about it. The good part is, Rabbi has moved away from his earlier image as a kind of Sufi/Sikh spiritualist, and is here singing about a much more earthly kind of longing (i.e., for a girl). But the bad part is, the song just isn't that exciting.

Fortunately, the rest of the album has some much more provocative material. I'm particularly impressed that Rabbi has taken on some political causes, including a very angry Hindi-language song about communalism, called "Bilquis":

For those who hadn't heard of Bilquis Yakub Rasool, here is a description of what happened to her during the massacre in Gujarat in 2002:

Also named in the song are Satyendra Dubey, a highway inspector who was killed after he tried to fight corruption, and Shanmughan Manjunath, killed in much the same way.

With songs like this, I see Rabbi as doing for Indian music what singers like Bruce Springsteen and Woody Guthrie have done in the U.S. -- documenting injustice, and telling the story of a society as they see it. It's vital, and necessary.

The album isn't all protest music, however. There is a surprisingly catchy and touching Punjabi song about a failed romance (is it autobiographical? I don't know) with a Pakistani woman, called "Karachi Valie":

And one other song I couldn't help but mention is Rabbi's rendition of a Punjabi folk song, "Pagrhi Sambhal Jatta," which names a long slew of Sikh martyrs, most of whose names I don't recognize (you can see the complete lyrics, in Punjabi and English translation, at the Avengi Ja Nahin website; click on "Music" and then on "Download Lyrics"). In an interview, Rabbi says he wrote his version of this song after an experience in London. I'm not quite sure what to make of the song yet, since I associate these types of "shahidi" songs with much more militant postures than Rabbi Shergill generally makes. (Note: there is also of course 1965 Mohammed Rafi version of "Pagri Sambhal Jatta," which you can listen to here; it's totally different).

From all the various Indian media sites that have done pieces on the new album, I could only find one honest review of the new Rabbi Shergill album, at Rediff. (I do think Samit Bhattacharya is a bit too unforgiving at times. Not every song on this album is highly memorable, but there are several that I find riveting...)

I'd also like to point readers to the Rabbi Shergill fan blog, Rabbism, which seems to be following the new album's release closely.

After a few years of silence (disregarding, for the moment, his contribution to the film Delhi Heights), Rabbi finally has a follow-up album, Avengi Ja Nahin (which would be "Ayegi Ya Nahin" if the song were in Hindi). The album is available at the Itunes store -- so if you're thinking of getting it, it should be easy enough to resist the temptation to download it illegally off the internets.

The video for the first single, "Avengi Ja Nahin", can be found on YouTube:

I'm personally not that excited about it. The good part is, Rabbi has moved away from his earlier image as a kind of Sufi/Sikh spiritualist, and is here singing about a much more earthly kind of longing (i.e., for a girl). But the bad part is, the song just isn't that exciting.

Fortunately, the rest of the album has some much more provocative material. I'm particularly impressed that Rabbi has taken on some political causes, including a very angry Hindi-language song about communalism, called "Bilquis":

Mera naam Bilqis Yakub Rasool (My name is Bilqis Yakub Rasool)

Mujhse hui bas ek hi bhool (I committed just one mistake)

Ki jab dhhundhhte thhe vo Ram ko (That I stood in their way)

To maen kharhi thhi rah mein (When they were looking for Ram)

Pehle ek ne puchha na mujhe kuchh pata thha (First, one asked me but I knew nothing)

Dujey ko bhi mera yehi javab thha (Then another but my answer was the same)

Fir itno ne puchha ki mera ab saval hai ki (Then so many that now I have a question)

Jinhe naaz hai hind par vo kahan the (Where are those who are proud of India)

Jinhe naaz hai vo kahan hain (Where are those who are proud)

For those who hadn't heard of Bilquis Yakub Rasool, here is a description of what happened to her during the massacre in Gujarat in 2002:

Bilqis Yakoob Rasool, herself a victim of gang-rape who lost 14 family members reported: "They started molesting the girls and tore off their clothes. Our naked girls were raped in front of the crowd. They killed Shamin's baby who was two days old. They killed my maternal uncle and my father's sister and her husband too. After raping the women they killed all of them... They killed my baby too. They threw her in the air and she hit a rock. After raping me, one of the men kept a foot on my neck and hit me."

A litany of institutional failures added to the suffering of women like Bilqis Yakoob Rasool and prevented justice being done against their assailants. During the attacks, police stood by or even joined in the violence. When victims tried to file complaints, police often did not record them properly and failed to carry out investigations. In Bilqis Yakoob Rasool's case, police closed the investigation, stating they could not find out who the rapists and murderers were despite the fact that she had named them earlier. Doctors often did not complete medical records accurately. (link)

Also named in the song are Satyendra Dubey, a highway inspector who was killed after he tried to fight corruption, and Shanmughan Manjunath, killed in much the same way.

With songs like this, I see Rabbi as doing for Indian music what singers like Bruce Springsteen and Woody Guthrie have done in the U.S. -- documenting injustice, and telling the story of a society as they see it. It's vital, and necessary.

The album isn't all protest music, however. There is a surprisingly catchy and touching Punjabi song about a failed romance (is it autobiographical? I don't know) with a Pakistani woman, called "Karachi Valie":

Je aunda maen kadey hor (Had I come another time)

Ki mulaqat hundi (Would we have still met)

Je hunda maen changa chor (Had I been a good thief)

Ki jumme-raat hundi (Would tonight have been a ball)

Je aunda jhoothh maenu kehna (If I knew how to lie)

Tan vi ki parda eh si rehna (Would this cover have still remained)

Hijaban vali (O veiled one)

Karachi Valie (O Karachi girl)

And one other song I couldn't help but mention is Rabbi's rendition of a Punjabi folk song, "Pagrhi Sambhal Jatta," which names a long slew of Sikh martyrs, most of whose names I don't recognize (you can see the complete lyrics, in Punjabi and English translation, at the Avengi Ja Nahin website; click on "Music" and then on "Download Lyrics"). In an interview, Rabbi says he wrote his version of this song after an experience in London. I'm not quite sure what to make of the song yet, since I associate these types of "shahidi" songs with much more militant postures than Rabbi Shergill generally makes. (Note: there is also of course 1965 Mohammed Rafi version of "Pagri Sambhal Jatta," which you can listen to here; it's totally different).

From all the various Indian media sites that have done pieces on the new album, I could only find one honest review of the new Rabbi Shergill album, at Rediff. (I do think Samit Bhattacharya is a bit too unforgiving at times. Not every song on this album is highly memorable, but there are several that I find riveting...)

I'd also like to point readers to the Rabbi Shergill fan blog, Rabbism, which seems to be following the new album's release closely.

Labels: Music, Politics, Punjabi, Secularism, Sikhism, Sufism